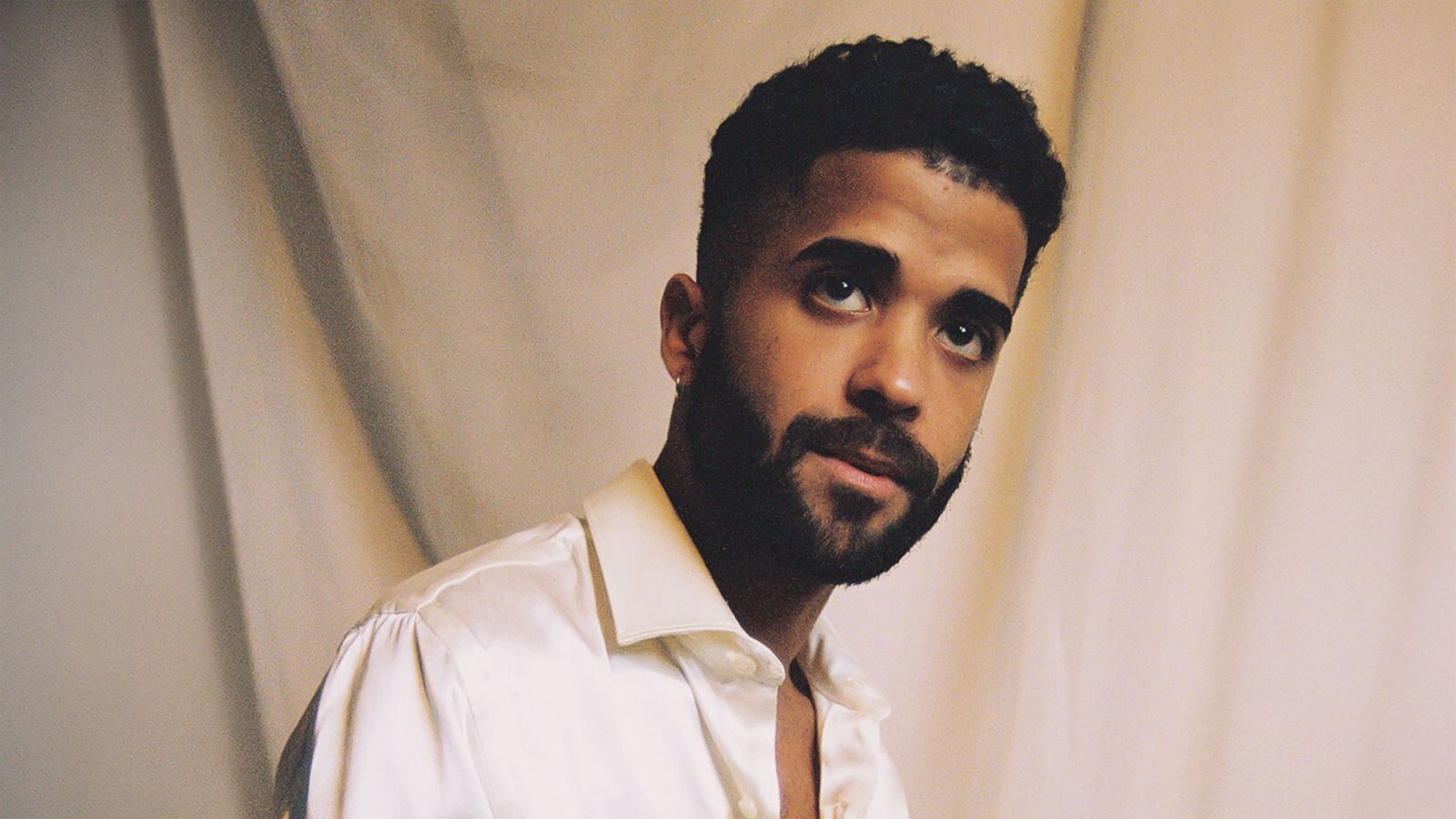

In a new occasional series for Hunter’s MFA Creative Writing Program, an alum will discuss their new book with a current student. Following, Alejandro Heredia ’23, a queer Afro-Dominican writer from The Bronx, speaks about his debut novel, Loca (Simon & Schuster) with Alisa Prude-Hunt ’25, a fiction student who is working on her first novel.

Prude-Hunt: Did you come to Hunter with this novel in mind? When did it start to take shape as a long-form project?

Heredia: I actually started this novel in 2018, a few years before Hunter. I was doing VONA [Voices of Our Nations Arts Foundation], a workshop fellowship program for writers of color, and they ask you to submit a short story. Some of the feedback that I got from that program was that it seemed like it should have been longer. So, I wrote the beginning of the novel and the end of the novel. And there was so much that had happened in between, where I did a time skip and everyone in the workshop asked that I spend more time with these characters.

Prude-Hunt: How did Loca change throughout your time at Hunter?

Heredia: I got feedback about the characters, how they were working, and some things that could be strengthened about them. In workshop with Sigrid Nunez — who was teaching at Hunter when I was there — she gave me some great feedback about writing men in a way that feels more complex and interesting than the way that I’d been writing some of the men in the novel. Especially Robert’s character, because he feels like such a … I don't know how he comes across now, but in the original version of the novel, he was such a villain.

Prude-Hunt: It’s interesting you say that about Robert, because I thought his portrayal was complex and so nuanced. I saw him as somewhat of an antagonist, but empathetic too.

Heredia: That was all thanks to workshop. I think sometimes us writers come to the page with our prejudices and baggage and ideas of the world that can get in the way of the writing. Workshop was really instrumental in allowing me to see the things that I was doing that I didn't know that I was doing. It brings craft to consciousness.

Prude-Hunt: “The body washes ashore at El Malecón salty and swollen, a brine of sorrow.” Your prose is so precise and evocative. What was it like finding your voice generally as a writer, and then, more specifically, finding the voice that best fits the needs of this particular novel?

Heredia: It just came out of so much revision. I lost count after a certain point because I had revised the entire novel so many times on the level of the sentence. I love sentences. That’s where I have the most fun, but that’s also what I find most challenging. Am I repeating myself too often? How do I use figurative language in a way that is expansive and doesn’t bog down the prose and distract from what I'm trying to say? I try to remember that clarity is the most important thing.

Prude-Hunt: Your work has been likened to Junot Díaz and Janet Mock. And the ambitious scope and thematics of Loca reminded me so much of James Baldwin’s Another Country. Who are some of your influences?

Heredia: I was reading a lot of writers from the Harlem Renaissance, like Nella Larsen and Claude McKay. Home to Harlem is a very complicated novel. Also, one of my favorite books — a book that is foundational to [Loca] is White Teeth by Zadie Smith. That was one of the first times that I saw a version of the world that I came from on the page. And obviously she's writing about London … but it felt very familiar to me because she's writing about the ways in which this cast of characters moves in, out, and through the neighborhood. That was really important for me to depict. I was raised in The Bronx in the early 2000s, and I included all those streets, images of the street vendors, the beautiful and challenging things. That’s why Charo, throughout the novel, feels claustrophobic. What I call the “Dominican Village” is comforting — it's very nice to belong to a community — but she also feels estranged from it. She feels like she can't be herself.

Prude-Hunt: Can you say a bit more about regionality?

Heredia: So much has been written about people from New York — but not from the perspective of the people who were born or grew up in the city. It was really important for me to center those people that have always been in New York.

Prude-Hunt: What was your research process like for places featured throughout the novel, like Santo Domingo, that you didn’t have easy access to as you were writing?

Heredia: It’s funny. Writing about Santo Domingo was a leap because I was born there, and I lived there until I was seven. I have some memory of it, but the rest of my life happened in The Bronx. Google Maps was really helpful, just allowing me to see how long it takes to get from this place to this place, where this park is, and where that monument is. Eventually I did go to Santo Domingo, right before the pandemic started in February of 2020, and it was helpful to be there and see all the things that I had been writing about to then make revisions. So, for example, one of the revisions that I made was about the statue of Christopher Columbus that appears in the novel. Right under it, there’s a statue of this woman — named Anacaona, a Taino leader — that was not in any of the images or any of the things that I was reading about online. I had to see it in person which formulated some of Yadiel’s ideas about resistance and making space for oneself in the world in resistance to what he calls ‘the conqueror.’ It was also helpful to go there and experience the Parque Duarte. It's one of the few public queer spaces that everyone knows is a queer space. It’s a safe space. People are able to just “be” there: gather, dance, listen to music. In the novel, there’s some tension between Sal and his friends and some of the aunties that hang out at the park. A part of what I was asking myself was — right now it’s a space of liberation — what might it have looked like fifteen, twenty, years ago?

Prude-Hunt: Loca contains such a rich cast of characters, and each manages to shine despite the ways in which their stories coalesce. What was it like getting into so many distinct characters’ head spaces?

Heredia: I think there’s an assumption that the characters that will come easiest to the author are the characters who share their “identities.” And so Dominican men should have been easy to write according to that logic. But in fact, I found a lot of the men in this story challenging to write precisely because I held prejudices about the men in my life, whereas women I’ve always seen as incredibly complicated, nuanced, interesting, and textured. That was what I hoped would transfer as I was writing folks like Ella, Charo and Yve. I wanted to challenge my prejudices and write characters that were nuanced. And so that’s where the inspiration to write a character like Don Julio came from, who — for a lot of the novel — feels like a very supportive person, a very kind person, a very giving person. I wanted to challenge this notion of the ‘Very Giving Uncle’ to show some of the work that it took for him to get there. Because for him it was a lot. I will also say that a lot of character writing is founded on intuition. You really have to be curious about people: people who are like you and people who are not like you. But it helps to have people also read it and tell you, “Hey, this sounds ridiculous.”

Prude-Hunt: Don Julio is such a compelling character. I’m curious about your decision to break away from the rest of Loca’s conventions for his backstory, which uses a collective ‘we’ voice in place of the third person narration used throughout the rest of the book. What inspired you to switch things up that way?

Heredia: I get bored when I'm writing a long project, of working within the same forms and formal rules. It was also a way for me to push on the page some of the ideas that I was trying to explore about community. I’m always interested in how people view outsiders or newcomers in a community. And, so, I thought that would be a really excellent way of exploring [Don Julio]. There were other chapters like that: one from Sal’s mother’s perspective that Adam [Haslett, director of the MFA program] read and said, “Hey, I see what you're trying to do here, but you don't really need this.” So, I ended up, thanks to Adam’s suggestion, taking that chapter out. But some of that voice became the impetus for a subsequent project I've been working on. Therein lies the power of revision. Sometimes we write great things into a novel that don't really belong in that novel; they belong in other projects.

Prude-Hunt: It’s exciting to know you’re working on something new! I can’t wait to read that when the time comes. Speaking of, I was so impressed with the ways you play with time throughout Loca. I think you were still in the cohort for Ayana Mathis’s craft seminar on uses of time in fiction. What was your approach to time as you wrote this novel, both structurally and in terms of the era it takes place in?

Heredia: First, thank you for saying that about the structure of the novel. It moves back and forth in time but doesn’t lay that out too explicitly. I like to challenge the reader, but I also like to trust that the reader is smart enough to keep up. My parents immigrated to The Bronx in the early to mid-90s. I really just wanted to capture that community and that wave of immigration because cities change so quickly, so on a very basic level I wanted to write a novel to suggest my people were here and this is the texture of their lives and what they were up to. I also wanted to take away the phone from the equation. I started writing this novel in my mid-20s and so I was dating a lot. I could have written a novel set in 2015, but because I was curious about my parents’ generation, I was also curious about what it would be like to not be on Tinder going on dates. What would it be like to just meet somebody at a bar or something like that? That’s why the novel begins with this meeting between Sal and Vance at the very end of that first chapter.

Prude-Hunt: I did really enjoy the immediacy of your scenes. Your decision to stick to the present tense, even in flashback, creates this sense of the reader building these core memories that inform the characters’ relationships right alongside them.

Heredia: I’ve been asked specifically why I write in the present tense and it’s because I like images. I feel like the most immediate way to write a powerful image is in the present tense — so, stylistically, it helps. But Loca is also about a group of people who have a lot of anxiety about the future, who are trying to not look back at their past … so that present tense is reflecting some of the ways in which they're trying to escape themselves. Especially for characters like Sal, considering the terrible experiences that they had back in their youth.

Prude-Hunt: Do your characters come to you or do you forge them?

Heredia: Characters usually come to me. I just start daydreaming about them; it's usually in the form of conversations. Sal and Charo were conceived in my mind at the same time because they were talking to each other all the time. I was really curious about what they were saying to each other, but also what they weren’t saying to each other. That’s why in that first conversation that they have in the novel, what they’re talking about isn’t revealed until later. They can't really talk about ‘the thing’ directly, so they’re talking around it. But, from the beginning, they came together — they came as a pair — which is why the novel ends up being about both of them ultimately.

Prude-Hunt: When did you know that Loca was complete?

Heredia: When it was snatched from my hands by my editor and my editor said, “You cannot touch this anymore!” Which is to say that if I could work on something forever, I probably would. So, it’s really healthy to know not when something is done, but when something is good enough to share with the next person — whether it’s a friend or a workshop or your professor or an agent or an editor. I think deadlines are good for writers.

Prude-Hunt: How has the publishing process differed, if at all, from your expectations? What’s your experience been like?

Heredia: It’s been complicated. I am incredibly blessed. I'm publishing a novel with a great editor at Simon & Schuster. And it's a dream come true in so many ways. I'm grateful for all the opportunities that have come my way in the last few years. I sold my novel even before graduating from Hunter, around March or April, right before I finished the program. And so, the feeling that I have is gratitude, but it has also been very challenging. I admire Adam for so many reasons. But one of the things that I think he's done such a great job of is protecting Hunter MFA students from the professionalism of writing. I remember him saying in more ways than one: all the professional stuff will come. But while you’re at Hunter, the most important thing to do is to focus on your writing so that when you leave here, you are as strong of a writer as you can be. Now that my book is about to come out, I really value that advice. The professional aspects of writing can be really soul-crushing. It can be very distracting. It can alter our definitions of success, and what we see as success for us as creatives and as writers. And so it is really important for you to know yourself as a person, as a writer, and to create a part of yourself that is unmovable — that is not moved by the market, that is not moved by likes on social media, that is not moved by anything else but your drive and your ambition on the page. You have to protect your relationship to your writing at all costs.

Prude-Hunt: How has your writing practice changed since you left Hunter?

Heredia: I miss getting feedback from eleven other people on my work, often. It’s really useful information. Not everything that everyone says in a workshop will be useful to you, even when they're good ideas. Someone may give you a really excellent idea that might just not fit your vision for the project. But all of it is clarifying for you to realize how people are responding to your work; how people are reading your work. And that is really instructive. I’ve been writing a lot the past few years because I've had the privilege of getting into writing fellowships back-to-back after graduating. From the time that I wake up to the time that I go to sleep, the most important thing that I have to do with my days is to write. So, I’ve been writing quite a lot. And it’s a little bit similar to when I first started writing Loca — just writing, writing, writing this project. It's just me and the page for a while.

Prude-Hunt: Do you have any advice for students in the program currently, those who are interested in applying, or for aspiring writers generally?

Heredia: I think a lot of people go into an MFA to try to figure out their writing practice. But I actually think that it’s most useful to have a sense of what your writing practice is before, so that when you’re in the program, you have a foundational idea of who you are, as a writer. That foundation allows you to be open to constructive feedback.